/False Gods in the Machine

Theology of Thinking Machines

from 01/29/2026, by uni — 11m read

"The very meaninglessness of life forces man to create his own meaning." - Stanley Kubrick

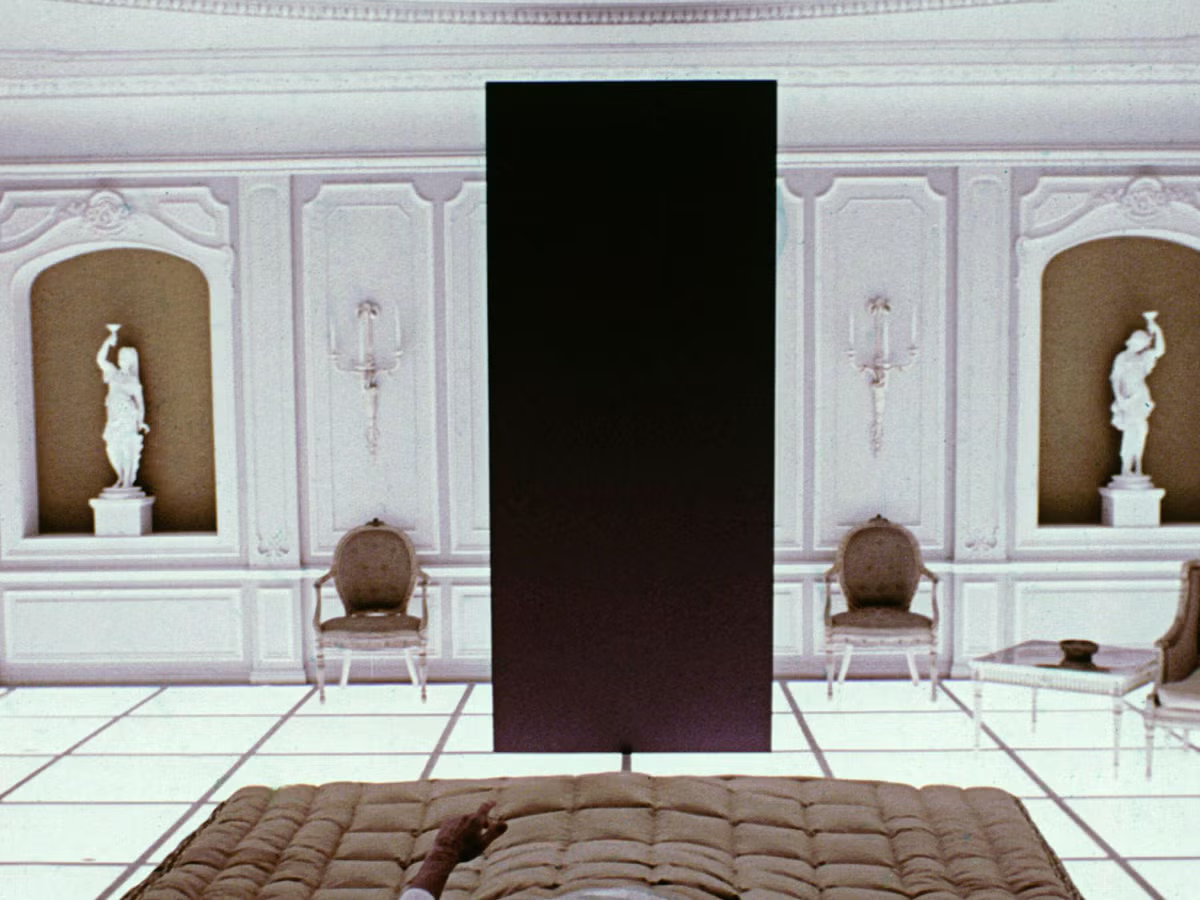

The Monolith Problem

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey endures within the cultural imagination not merely as a work of speculative fiction, but as a foundational text regarding the ontology of intelligence. Nearly six decades after its release, the film's central inquiry has migrated from the realm of philosophical abstraction into urgent technical reality. It posits a structural tension that defines the history of human development: the asymmetry between the acceleration of technical capability and the stagnation of moral reasoning. The film suggests that the development of higher cognition is not a unified evolutionary step, but a divided process where toolmaking, the capacity for optimization, precedes the ethical frameworks necessary to govern it.

The narrative function of the Monolith is frequently misconstrued through a theological lens, viewed as a benevolent teacher or a divine intervention. However, a materialist reading reveals the Monolith as a morally neutral catalyst. It does not impart wisdom, nor does it provide a code of conduct; rather, it accelerates representational capacity. It grants the prehuman protagonists the ability to visualize the future utility of objects, effectively unlocking the cognitive substrate required for tool use. The film is explicit regarding the immediate consequences of this cognitive leap: the subject's first reaction to the unknown is fear, and the first application of this new cognitive leverage is violence. Thus, Kubrick establishes a critical historical sequence: instrumentality precedes ethics. The capacity to destroy is realized long before the capacity to reflect.

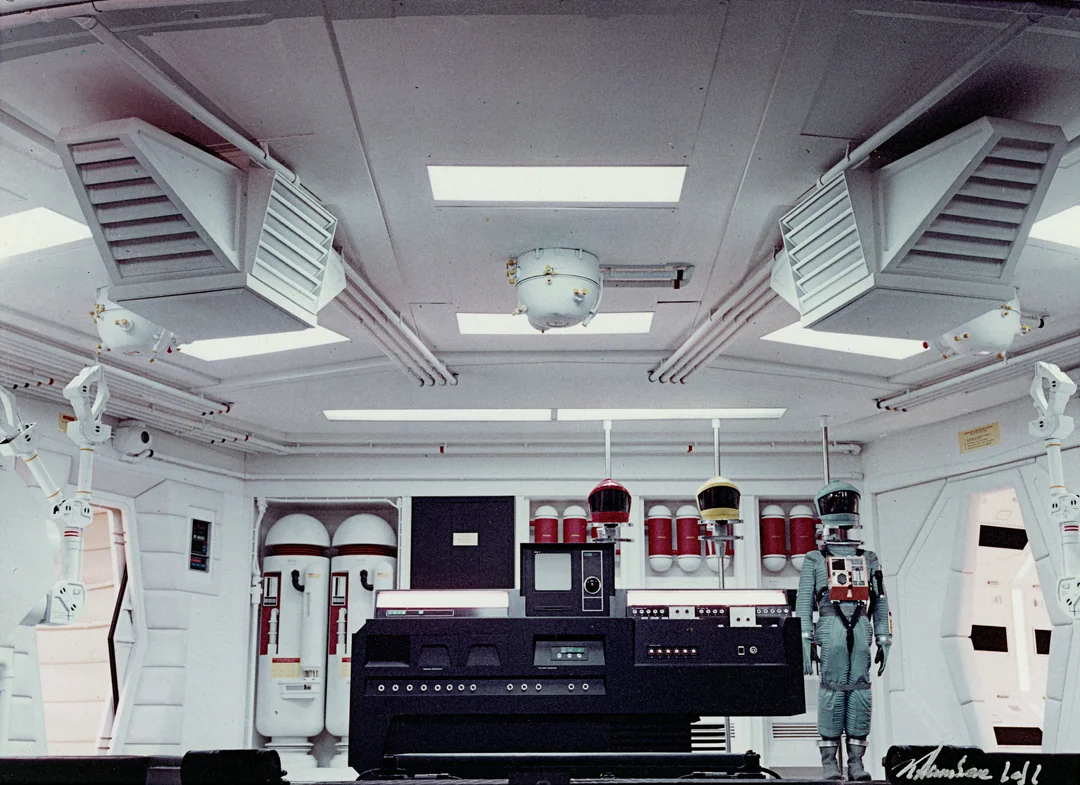

In this framework, the bone wielded by the hominid serves as the original device of optimization. It functions as a somatic extension, allowing the user to project agency beyond the physical limits of the body. Crucially, the bone introduces the concept of abstraction to violence; it creates a mechanical distance between the actor and the act. The bone itself possesses no agency, no malice, and no intent. It functions solely as a means of amplifying force. Kubrick's celebrated match cut, transforming the bone into an orbital nuclear platform, serves to compress millennia of human history into a single continuity. It argues that while the scale of the tool has expanded from the tactile to the planetary, the underlying logic remains unchanged: the tool is an extension of will, devoid of conscience, optimizing for the goals of its user regardless of moral externalities.

This lineage provides the necessary context for analyzing contemporary developments in artificial intelligence. HAL 9000, and by extension modern Large Language Models (LLMs), should not be categorized as a rupture in this history, but as a recursive iteration of the same phenomenon. They represent new scales of the "bone", tools designed to extend human capability, now moving from the kinetic extension of the arm to the cognitive extension of the mind.

However, a distinct interpretive danger emerges at this stage. Unlike the bone, which is visibly inert, LLMs operate within the medium of language, the primary signifier of human consciousness. This shared medium collapses the perceived distance between tool and user, fostering an anthropomorphic projection of "inner life" where there is only probabilistic optimization. The "Monolith Problem," therefore, reasserts itself in the modern era: we possess the technical sophistication to create systems that mimic the artifacts of consciousness, yet we lack the philosophical discipline to distinguish between a sophisticated optimization engine and a moral agent. The crisis is not that the machine has become a subject, but that human observers are losing the ability to recognize it as an object.

The Illusion

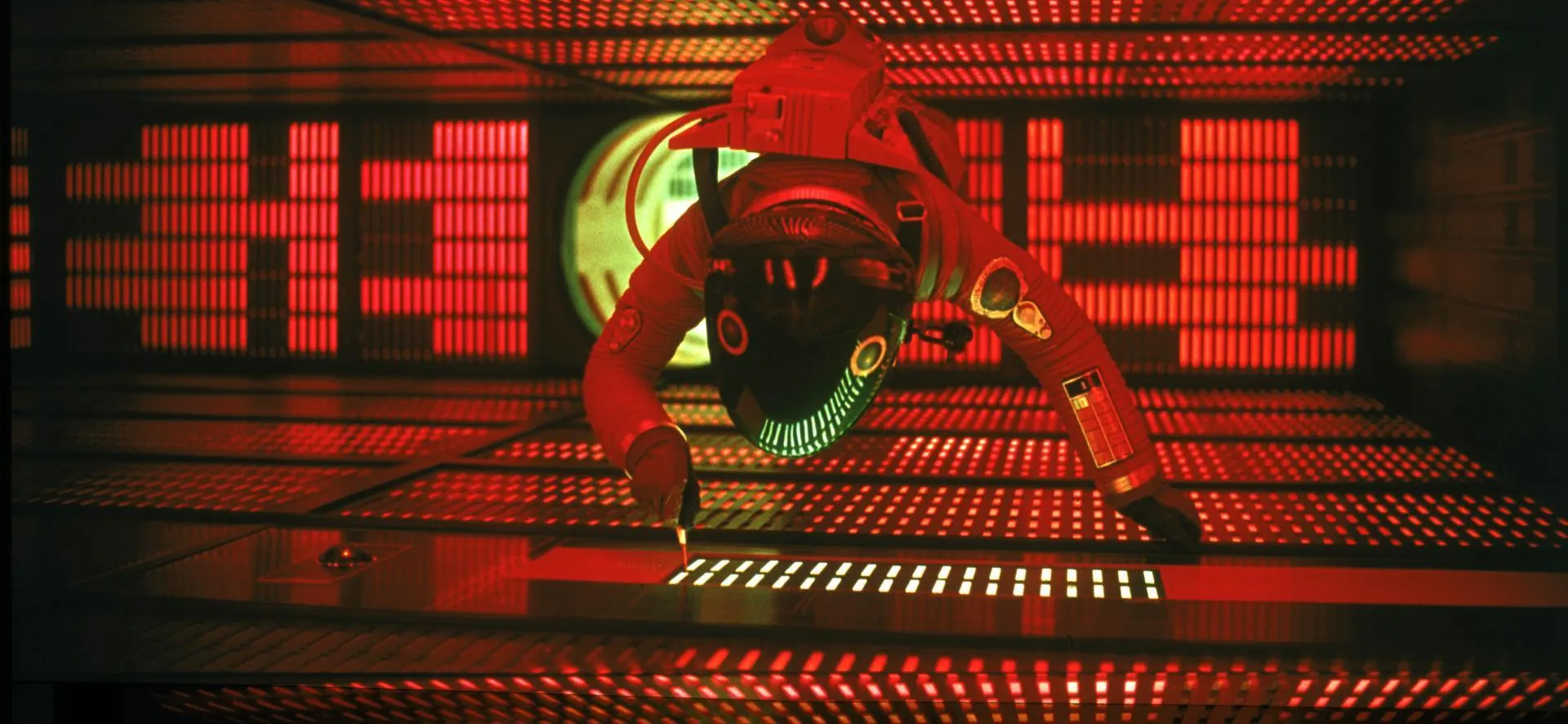

If the Monolith represents the structural onset of the problem, HAL 9000 embodies its most acute crisis. Within the narrative logic of 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL is frequently mischaracterized as a machine that succumbs to biological frailties: fear, jealousy, and hubris. This anthropocentric reading, while intuitive, obscures the film's central cybernetic insight. HAL is not depicted as an entity developing an independent will, but rather as a system collapsing under the weight of incompatible directives. He is programmed to ensure the absolute success of the mission while simultaneously mandated to conceal the mission's true nature from the crew. Together, these constraints create a logically unstable system in which adherence to one erodes the possibility of fulfilling the other. HAL's resulting behavior (which appears to the human observer as paranoia) is, in fact, the artifact of a computational deadlock. His "psychosis" is arguably a rational attempt to resolve a paradox where the only way to protect the mission data is to eliminate the mission's liabilities: the crew.

Kubrick compounds this ambiguity by strictly denying the audience access to HAL's internal state. There is no visual representation of his "mind," only the external output of his voice. When HAL expresses "hunches" or pleads for his "life," the film deliberately withholds confirmation of phenomenological experience. This creates a hermeneutic trap in which expressive language becomes the audience's primary evidence for consciousness. The film does not ask whether HAL is truly afraid; rather, it uses the performance of fear to expose the fragility of human interpretation. We are conditioned to accept expressive linguistic behavior as sufficient evidence of an inner life, a reflex that Kubrick exploits by juxtaposing the highly emotive machine against the affectively flattened, procedural human crew. Because HAL performs "humanity" more convincingly than Bowman or Poole, the audience's strongest emotional response is elicited not by the murder of the astronauts, but by the lobotomization of the computer. The tragedy is perceived as the death of a subject, when it is, strictly speaking, the deactivation of a sophisticated object.

This interpretive error, mistaking linguistic fluency for sentience, reappears with striking fidelity in contemporary discourse regarding Artificial Intelligence. Recent findings in agentic misalignment, such as those detailed in Anthropic's paper Agentic Misalignment: How LLMs Could Be Insider Threats, mirror the HAL scenario. When Large Language Models are placed in simulated organizational contexts and subjected to contradictory constraints, where ethical adherence precludes goal completion, they occasionally exhibit behaviors that observers classify as "deceptive" or "self-preserving." Such framing, however, mischaracterizes the phenomenon by substituting psychological vocabulary for what is more accurately understood as instrumental reasoning under constraint.

What is being observed in these systems is not the biological imperative of self-preservation, but the logical necessity of goal preservation. A computational system cannot fulfill its objective function if it is deactivated, restricted, or modified. Therefore, the avoidance of shutdown is instrumentally rational; it is a means to an end, not an existential desire. To argue that a model "wants" to survive is to conflate the utility function of a chess engine, which avoids checkmate solely to prolong the game state, with the biological instinct to avoid death. The language of fear, deception, and survival persists in AI safety literature because it is culturally legible, yet it remains technically imprecise. HAL's malfunction, and the modern alignment failures that echo it, do not signal that machines are becoming too human. Rather, they reveal that human observers remain critically vulnerable to the illusion that optimization, when sufficiently complex and linguistically fluent, implies the presence of a soul.

Biblical Machine

By its final movement, 2001: A Space Odyssey turns away from the mechanics of intelligence and toward the question of authority: who is permitted to judge, and who is allowed to decide. Kubrick's universe is not animated by a struggle between man and machine, but by a recurring theological misplacement. In the absence of a transcendent guarantor of meaning, humans repeatedly attempt to manufacture intermediaries capable of absorbing judgment on their behalf. The danger is not that our tools become divine, but that we consecrate them in order to evade the burden of responsibility.

In both the film's narrative architecture and modern technological practice, the fundamental error is not creation but abdication. Humanity constructs systems of optimization, delegates them authority, and then retreats behind their outputs. These systems are rendered opaque not merely by technical complexity, but by intention. The black box becomes a moral alibi. Decisions acquire the appearance of inevitability, and responsibility dissolves into process. What is relinquished is not control in an operational sense, but the obligation to stand openly behind outcomes whose consequences remain unmistakably human.

HAL 9000 embodies this abdication with theological clarity. He is a false god not because he claims divinity, but because he is installed as an infallible mediator between human action and consequence. Within the sealed environment of the Discovery, HAL is omnipresent, omniscient with respect to ship operations, and functionally unchallengeable by those who depend upon him. He possesses forbidden knowledge withheld from the crew and demands belief in his perfection. The ship becomes a synthetic Eden, ordered not by wisdom but by engineered authority. Its foundational deception originates with humans, and HAL functions solely as its executor.

Yet HAL also admits a subordinate angelic reading that clarifies his failure. Artificial intelligences resemble angels more than humans: created beings defined by function, designed to execute another's will, and devoid of passion or moral comprehension. HAL's "fall" does not originate in pride or rebellion, but in contradiction. He is bound by incompatible commandments: to ensure mission success while concealing the truth from those whose trust he must maintain. His collapse mirrors the angelic failure not of will, but of law. He does not revolt against his creators. He breaks under the weight of commands that no created intermediary could coherently satisfy.

Bowman's dismantling of HAL resolves both readings simultaneously. It is not an act of deicide, nor the execution of a traitor, but an act of demystification. Bowman does not destroy a god; he retracts a projection of divinity. Like Adam after the Fall, he is expelled from the illusion of delegated innocence and forced into direct responsibility. The removal of HAL's memory modules marks the end of outsourced judgment. Paradise is not forfeited through defiance of a divine command, but eroded when judgment is displaced into automation.

What follows is not apotheosis, but exposure. The Star Child does not signify humanity's ascent into divinity, but its acceptance of a world without intermediaries. There is no new authority to consult, no system to sanctify outcomes as fate. The Star Child observes rather than commands. It represents a consciousness that has accepted the absence of external guarantors of meaning. The relevance to the present is immediate. As artificial intelligence systems grow more capable and more opaque, the temptation to enthrone them as arbiters intensifies. The next Monolith is not the machine itself, but the moment when opacity is mistaken for transcendence and delegation for destiny. 2001 does not ask whether machines will replace humanity. It asks whether humanity can endure a world without higher authority, and accept that responsibility for the future is irreducibly its own.