/A1000

Harmony in a Machine

from 10/24/2025, by uni — 11m read

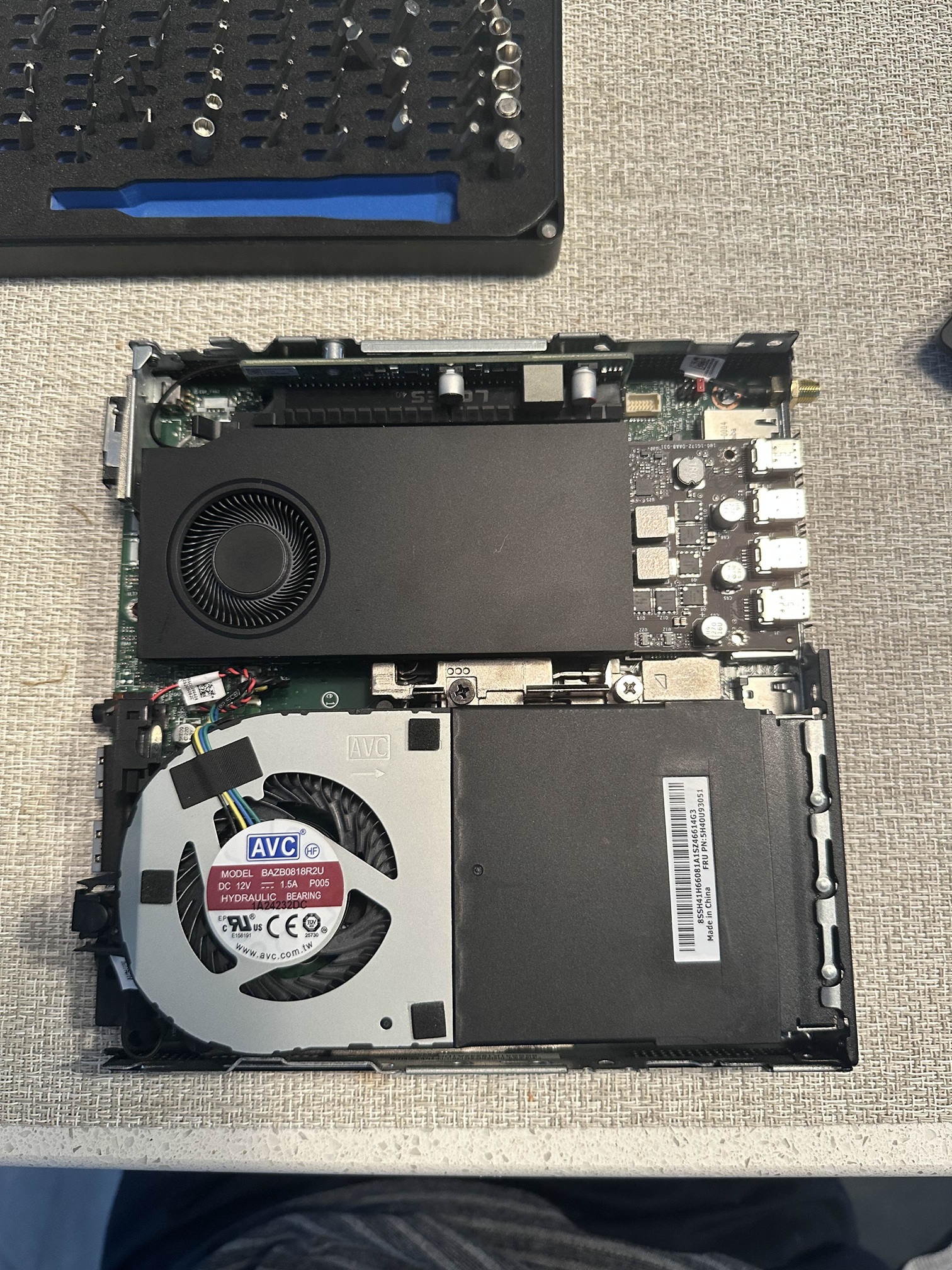

A1000

After several weeks of hesitation, I finally caved and bought a replacement for my restless Yeston RTX 3050. That card had been a constant nuisance, loud, inconsistent, and seemingly incapable of composure. I wanted something quieter, yes, but more than that, I wanted a part that embodied restraint. I was caught between two affordable contenders, the Sparkle Intel Arc A310 ECO and the XFX Speedster SWFT 105 RX 6400, both single-slot cards that could slot neatly into my Lenovo P3 Tiny. Neither promised any remarkable power, yet each represented a sort of humble engineering honesty. But even in their modesty, they fell short: too weak to justify, too uncertain to trust. What I sought wasn’t power, but clarity, precision, and composure. Such harmony is uncommon in consumer hardware.

For days I wavered, comparing specs, asking around online, looking for anyone who had walked the same path of over-optimization. Then I found a build that mirrored my own: a ThinkStation Tiny transformed into a compact workstation through a custom RTX A2000 paired with a N3rdware single-slot cooler. It was an audacious little build, dense, intentional, and impressively contained. The owner had sacrificed thermal headroom for elegance, and though reviews mentioned the card ran hotter, the design discipline spoke to me. Still, the lingering issue was noise, and at over $550, the A2000 felt like a beautiful but misguided overreach.

Then came its quieter sibling, the RTX A1000, a card I hadn't paid attention to because it existed between categories, not glamorous enough for gamers, not powerful enough for professionals. But in that gap it achieved something better: balance. Its form factor was ideal for the Lenovo chassis, and its efficiency made it far more practical than any consumer GPU I'd been considering. My confidence solidified after a brief message exchange with a user who described it as "silent for me." I didn't need further persuasion. The Yeston still retailed for around $210, while most A1000s were closer to $350, but I found one used for $299. The upgrade followed no logic of performance or value. It came from a sense of aesthetic order that numbers could never justify. I wanted a component that could simply disappear into the system and let the machine breathe again.

Figure 1: RTX A1000

Figure 1: RTX A1000

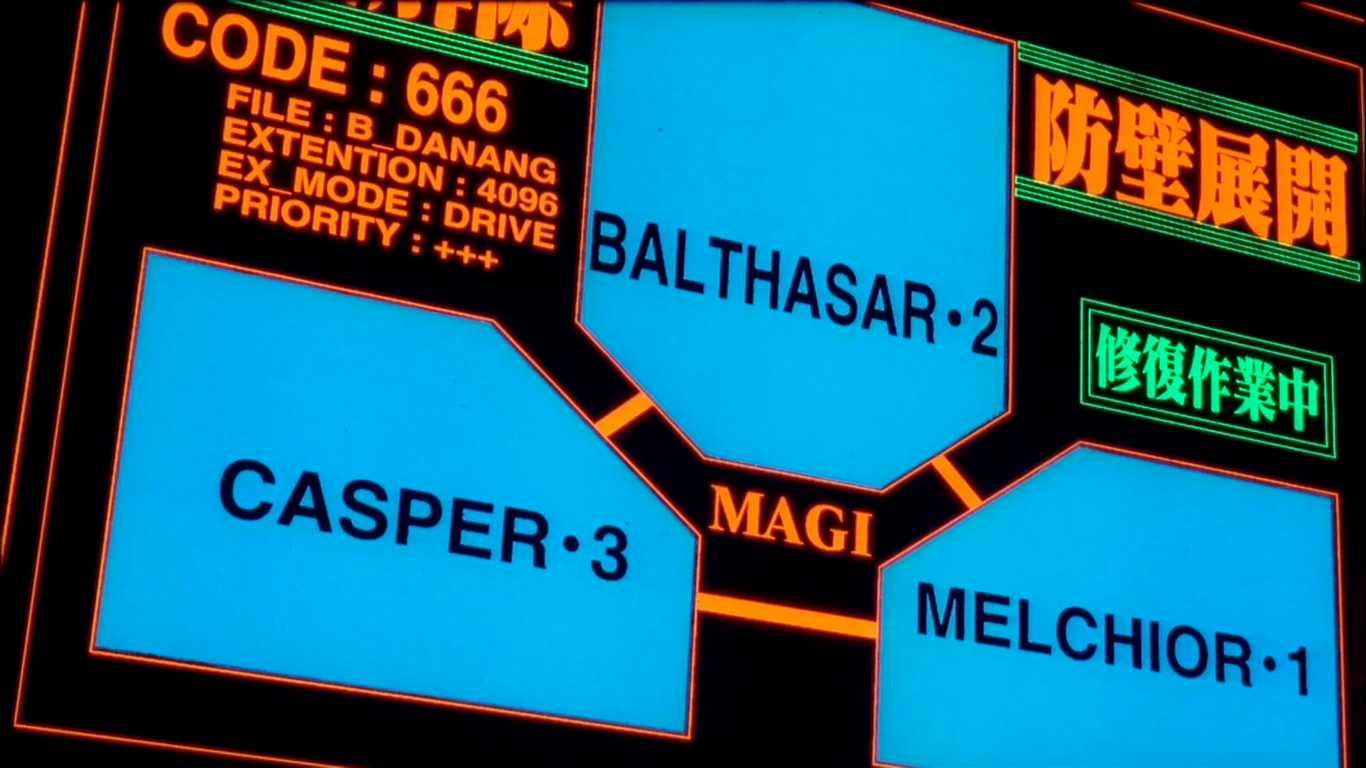

While waiting for it to arrive, Magi, as I'd named the system, was reduced to a passive entertainment box, playing Breaking Bad in the background. The irony wasn't lost on me: a machine designed for experimentation now doing nothing but idling through digital noise. When the A1000 finally came, I approached it with cautious excitement. The card was striking in its simplicity, industrial, refined, almost serene. No gaudy branding or plastic curvature, no illusion of performance through aesthetics. Just aluminum, circuitry, and intent. In my hands, it felt like a reminder that excellence in hardware lies not in display, but in the quiet precision of its purpose.

Installation was uneventful, which in the world of small-form computing is a victory in itself. Once powered on and initialized, the transformation was immediate. The fan spun up, found its equilibrium, and stayed there, steady, constant, unintrusive. The system no longer breathed erratically; it exhaled. Even without a 0 RPM mode, the noise was uniform and dignified, absorbed into the gentle static of daily life: the hum of the refrigerator, the pulse of the HVAC, the distant steps of neighbors. For the first time in months, the system felt finished. I nudged it deeper under the console, not to hide it, but to let it exist, quiet, confident, and complete.

Figure 2: MAGI - P3 Tiny

Figure 2: MAGI - P3 Tiny

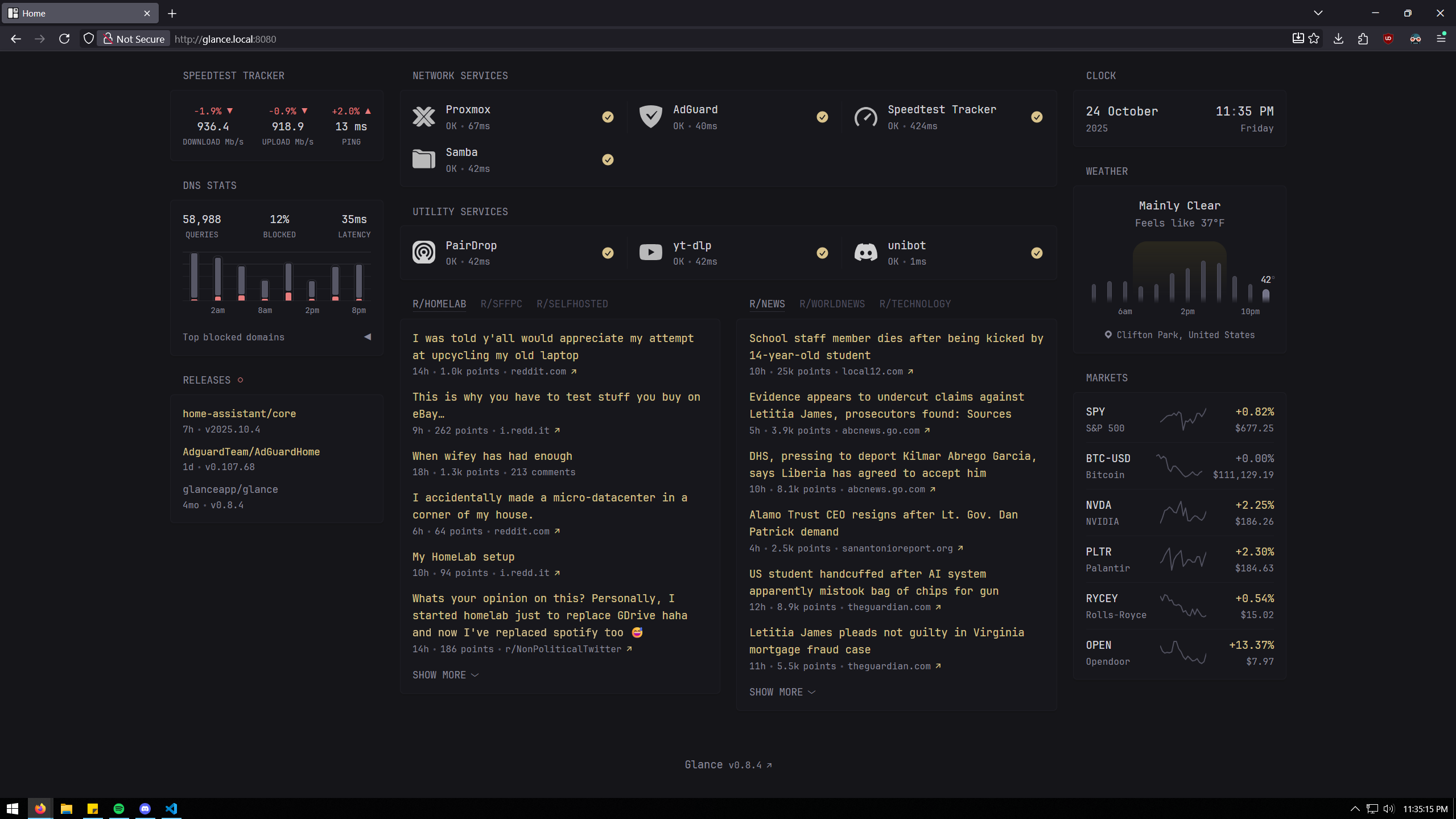

MAGI

With the hardware in harmony, I turned my focus back to the soul of the system, its structure and logic. The foundation remained the same: Proxmox as the governing layer, orchestrating a network of virtual machines and containers. But what changed was how I began to see it. The system had grown beyond a set of utilities, taking on the coherence of a living architecture. Each layer existed with purpose and restraint, mirroring the triadic design of its namesake: the Magi System from Neon Genesis Evangelion. In the series, the Magi were three parallel computers that represented the conflicting dimensions of human decision-making, scientific, moral, and emotional. My setup echoed that metaphor, intentionally or not: three "brains" governing three distinct modes of operation.

Figure 3: MAGI from NGE

Figure 3: MAGI from NGE

The first brain was the Windows 11 VM, passed through the A1000, serving as the visual and interactive layer, the human interface. It ran the media console, streamed content through Stremio, and handled live sports through REDACTED. It was the most visible part of the machine, yet it revealed nothing of its complexity. The illusion was perfect: to anyone using it, this was simply a fast, silent living room PC. The virtualization layer was invisible, and that invisibility was part of its beauty. It reminded me that good computing doesn't announce itself, it recedes, letting form follow function until the machine becomes a natural extension of life.

I'd considered adding Jellyfin as a self-hosted alternative to Plex, but Stremio's efficiency kept me from doing so. It aggregates, it streams, it just works. I don't need to collect terabytes of media when the architecture itself already embodies the idea of curation. There's an elegance in knowing when to stop, when not to fill your drives, when not to chase redundancy for its own sake. Minimalism in software is often more radical than minimalism in design.

The second brain was the Debian VM, the computational center. This is where Docker runs, managing containers that don't fit neatly into LXC. Here live two of my current projects: Speedtest Tracker, which quietly logs every fluctuation in my network's pulse, and unibot, my personal Discord bot. The latter represents something deeply satisfying to me: the ability to create a digital entity that mirrors my interests, automates my habits, and reports back to me on the rhythms of my own systems. Developing in a clean, isolated Linux environment keeps the logic pure, no cluttered dependencies, no interference from my main desktop. It's computing as it should be: deliberate, organized, and separate from the noise of daily use.

Then there are the LXC containers, small self-contained fragments of function that perform single roles: AdGuard Home for DNS-level filtering, yt-dlp WebUI for remote video management, and others waiting in the wings. LXCs are the most elegant abstraction I've found in modern computing, they embody the Unix philosophy perfectly. Each container does one thing and does it well, decoupled yet connected through the hypervisor's quiet logic. When one fails, it doesn't poison the others. It's a reflection of modular design as philosophy: self-sufficiency without isolation.

Setting all of this up on Proxmox was an education in clarity. The software has a certain academic rigor to it: spartan but transparent, like a well-designed research instrument. I leaned heavily on the Proxmox Helper Scripts maintained by the community. These scripts are more than shortcuts, they're the codified wisdom of hundreds of users who came before me. The PVE Post Install script, for instance, cleans and optimizes the system, while the Intel e1000e NIC Offloading Fix repairs a long-standing driver issue. They are acts of generosity in code form, the open-source ethos distilled into scripts that ask for nothing and give everything.

Figure 4: My custom Glance Dashboard

Figure 4: My custom Glance Dashboard

To tie it all together, I use the Glance Dashboard, a web interface that gathers every container, VM, and service into one coherent view. Configuring it was a quiet exercise in patience: YAML adjustments, API endpoints, header templates. But once complete, the result was deeply satisfying. A single page that maps my entire digital ecosystem. Each tile, each metric, represents a decision, a small piece of order carved out of chaos. I check it not because I need to, but because it feels like looking at a finished painting, a balance of function and form.

Eventually, I plan to integrate Home Assistant into Magi. Not as a step toward gadgetization, but as an experiment in control. Living in an apartment limits what I can automate, but even simple integrations, a smart bulb, a camera, can serve as small proofs of concept. What interests me isn't the convenience, but the orchestration: the ability to make systems converse with each other in a local, closed loop. Home automation, stripped of consumerism, becomes an exploration of autonomy.

Closing Thoughts

When I step back and look at Magi now, it feels less like a homelab and more like a discipline. Each part exists for a reason, each service occupies its own boundary, and each process reflects a small act of design. There's beauty in that deliberation. Computing, when done with care, begins to resemble architecture: a balance of structure, proportion, and quiet intention. It moves beyond performance and functionality, toward the arrangement of systems into something coherent and self-sustaining.

In an age of relentless upgrades, refinement feels almost radical. The A1000 doesn't boast; it serves. Proxmox doesn't seduce; it endures. Together they form a kind of mechanical harmony, a network of rules and routines that coexist gracefully, humming beneath the surface of ordinary life. That, to me, is the real beauty of computing: not the spectacle of innovation, but the quiet pursuit of perfection within limits. Efficiency fades with time, but coherence endures. That is the quiet mark of a system built with intention.

The Magi Project stands as a reminder that computing at its best isn't about what it can do, but how it's done. It's a dialogue between logic and aesthetics, between the tangible and the conceptual. Every decision, from GPU choice to VM configuration, reflects an underlying belief: that technology, when crafted deliberately, can be as elegant as any art form. And in that small, humming Lenovo case under my media console, I've built something that reminds me why I fell in love with computers in the first place.