uni's digital archive

Just Judges

Art, Politics, and the Six-Century Mystery of Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece

from 30/09/2025, by uni — 37m read

Figure 1: Hubert and Jan van Eyck - Ghent Altarpiece (1432)

Figure 1: Hubert and Jan van Eyck - Ghent Altarpiece (1432)

Exposition

The arrival of oil painting in Northern Europe in the early fifteenth century marked a revolution in art, altering not only how images were made but how they could embody devotion, memory, and power. Prior to van Eyck, egg tempera was the dominant medium, limiting the subtlety of light, shadow, and texture that painters could achieve. Oil allowed for slow drying, glazing, and layering, creating luminous depth and hyper-realistic detail that rivaled human perception itself. In the Ghent Altarpiece, oil painting became a theological medium, translating divine mystery into visible, tangible form. The gleaming surfaces, the naturalistic landscapes, and the microscopic attention to textures of cloth, hair, and skin elevated sacred figures into a palpable reality. For the faithful, this was not art for art's sake but an instrument of devotion: a portal where the divine was made visible through material precision.

The grandeur of the altarpiece lies in its scale and complexity. Composed of 12 main panels when fully opened, it stages a cosmic theater: God enthroned, the Virgin and John the Baptist as intercessors, angels singing and playing instruments, and a vast assembly of saints, prophets, and pilgrims converging on the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. The hinged, monumental panels were conceived as a liturgical performance in paint, opening on feast days to unveil their overwhelming brilliance. This dynamic structure mirrored the mysteries of Christian theology: concealment and revelation, sin and redemption, absence and presence. To encounter the Ghent Altarpiece was to be confronted with both the majesty of divine truth and the dizzying scope of creation itself.

This artwork must also be situated in the volatile political landscape of early 15th-century Northern Europe. The Burgundian Netherlands, under Philip the Good, had emerged as a nexus of wealth and power, benefiting from trade routes and urban prosperity in cities like Ghent and Bruges. Yet this prosperity was shadowed by political instability. The Hundred Years' War continued to destabilize France and England, while the Burgundian dukes sought to consolidate their dominion over a patchwork of territories. Patrons like Joos Vijd acted within this context: civic leaders aligning themselves with the ducal court, using monumental commissions to cement both spiritual salvation and worldly prestige. Around 1420, Joos and his wife Elisabeth Borluut endowed their private chapel within Saint John's (later Saint Bavo's) Cathedral, and it was Joos who formally commissioned Hubert van Eyck to design and begin the immense polyptych. Hubert, a member of the cathedral's minor clerical orders, conceived the framework of the project before his death in 1426, leaving Jan to carry it to completion. The altarpiece thus functioned simultaneously as a devotional object and a political statement, binding Ghent's religious and civic identity to Burgundian power.

The theological and political ambitions of the time converge in this single masterpiece. By combining naturalistic oil technique with overwhelming iconography, Hubert and Jan van Eyck transformed painting into an articulation of both divine and worldly order. The Ghent Altarpiece gave visual form to an age struggling to reconcile faith, wealth, and political ambition. Its sheer presence in Saint Bavo's Cathedral embodied the aspirations of patrons, clergy, and dukes alike: eternal salvation for the soul, enduring legacy for the family, and the projection of Burgundian power across a fragmented Europe. In this sense, the Just Judges panel belongs to a larger program that bound together artistry, theology, and politics in an overwhelming vision of order and devotion.

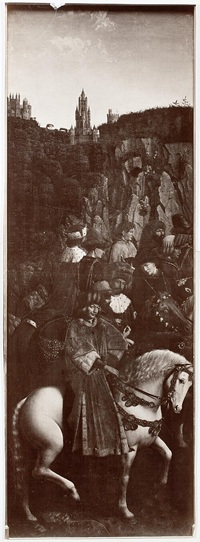

Figure 2: Jan van Eyck - Just Judges (1432), Photo of original

Figure 2: Jan van Eyck - Just Judges (1432), Photo of original

Click here to view a super high resolution image of the panel.

Fragmentation

The turbulent history of the Ghent Altarpiece reflects Europe's own centuries of conflict, conquest, and shifting ideologies. From the very beginning, its fame made it a target. Individual panels were detached and sold off in the 16th and 19th centuries, ending up in the hands of monarchs and collectors who saw them as trophies of culture. Napoleon, ever hungry to centralize Europe's treasures in Paris, had the work seized during his campaigns, though it was later returned after his defeat. In the 20th century, the painting's ordeal intensified: first dismantled and censored during periods of religious strife, later stolen by the Nazis for Hitler's planned "super museum" in Linz, and finally concealed in an Austrian salt mine before being recovered in a dramatic rescue by the Allied Monuments Men in 1945. Few works of art embody the political instability of Europe as vividly as the Ghent Altarpiece, whose panels were shuffled like pawns in a geopolitical game.

Amid this history, the Just Judges panel occupies a unique place, not only because it is the sole missing piece but also because its symbolism cut to the heart of both civic and spiritual authority. Its imagery of monarchs, princes, and noblemen, all dressed in opulent attire but proceeding humbly toward the Lamb, encapsulated the submission of temporal power to divine order. To the citizens of Ghent, the panel was a mirror of their lived position, suspended between ducal authority and God's church. The panel reinforced the cathedral's role as a space where civic pride and religious devotion converged, binding rulers to the same universal order that governed the lives of commoners. The absence of this panel tears through the narrative thread that bound worldly justice to sacred destiny.

The 1934 theft of the Just Judges elevated the altarpiece from revered artwork to modern legend. Unlike other panels lost through sale or war, this one vanished into a web of intrigue and unresolved mystery. Its disappearance transformed the painting into a symbol of fragility in the face of human greed and ambition, while also creating a narrative of obsession that continues to this day. Scholars, detectives, and conspiracists alike have combed through archives, suspect lists, and hidden clues, but the panel has never resurfaced. In Saint Bavo's, the replica does not resolve the absence; the void it conceals embodies the fragile bond between power, justice, and human fallibility. The Just Judges, once a visual reminder of submission to God's law, has itself become a cautionary tale of how human authority can twist, steal, and erase what was meant to transcend it.

10

Figure 3: Right: Manuscript portrait by Thomas Hoccleve (1412)

Figure 3: Right: Manuscript portrait by Thomas Hoccleve (1412)

The Poet

Geoffrey Chaucer's career offers the perfect precedent for van Eyck's vision in the Just Judges. Chaucer was both the father of English poetry and a court official who survived the volatile reigns of Edward III, Richard II, and Henry IV by wielding the power of language and narrative. His Canterbury Tales, begun in the 1380s, provided a radical new literary structure: a pilgrimage in which each participant is simultaneously an individual and a type, a singular voice and a social role. The Knight appears both as a flesh-and-blood veteran of campaigns and as the allegory of chivalry itself; the coarse, hard-drinking mill worker becomes not only a rustic character but the embodiment of vulgar appetite. This layering of identity, where the reader is asked to see many meanings in one figure, became Chaucer's enduring innovation.

Van Eyck transposes this narrative method directly into the Just Judges. The ten horsemen riding toward the Adoration of the Lamb are not stable portraits of specific rulers or saints but composites designed to bear multiple identities. The man in the orange cowl, identifiable as Chaucer, is emblematic of this strategy: he may be a poet, a bureaucrat, a judge, or all three at once. Each face in the panel invites multiple readings, just as each pilgrim in Chaucer's tale is more than they first appear. This allows van Eyck to suggest a far larger procession than the panel actually depicts. Ten figures in the Just Judges may echo Chaucer's pilgrims, each of whom was intended to tell four stories, multiplying individual characters into a larger, unfinished tapestry. Multiplicity becomes the visual language of universality, compressing earthly diversity into a unified movement toward the divine.

By adopting Chaucer's principle of layered identity, van Eyck transformed what could have been a static procession of noblemen into a dynamic interplay of narrative possibilities. To a Ghent burgher, one judge might resemble a local civic leader; to a Burgundian courtier, the same face could evoke a duke or knight; to a cleric, it was an allegorical ruler submitting to God. The ambiguity was not a flaw but the panel's greatest strength. It allowed the altarpiece to speak simultaneously to multiple audiences while maintaining its theological coherence. Just as Chaucer's pilgrims traveled together toward Canterbury, van Eyck's judges converge toward the Lamb, their overlapping identities merging earthly authority and spiritual truth into a single, inexorable procession.

The Artists

Figure 4: Hubert and Jan van Eyck

Figure 4: Hubert and Jan van Eyck

The inclusion of Jan and Hubert van Eyck at the center of the Just Judges panel functions as both a signature and a statement of artistic authority. Van Eyck rarely placed himself directly into sacred compositions, but here, flanked by his brother, he inscribes the artists into the very procession of justice. The resemblance between Jan's figure and his 1433 Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban is unmistakable, and art historians have long considered these the only two true self-portraits of the master. His choice to echo the turbaned likeness in the Just Judges collapses the boundary between the sacred narrative and the personal history of its maker. Hubert's presence beside him, adorned with a pearl brooch and positioned in seniority, is equally deliberate: a reminder to posterity that the elder brother was the original architect of the altarpiece, even if death prevented him from seeing it to completion. Their joint depiction in a panel that grapples with justice suggests that the van Eycks understood artistic creation itself as a form of judgment, binding together memory, interpretation, and legacy.

Figure 5: Right: Jan van Eyck - Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (1433)

Figure 5: Right: Jan van Eyck - Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (1433)

The figure to Jan's right complicates this fraternal portrayal. Scholars have long debated whether this enigmatic presence is their half-brother Barthélemy van Eyck or one of the Limbourg brothers, most likely Paul. Both candidates were deeply entwined in the same networks of manuscript illumination that trained and influenced the van Eycks. Barthélemy's documented work on the Turin–Milan Hours and the later completion of the Très Riches Heures connects him directly to John, Duke of Berry's ambitious artistic commissions. The Limbourg brothers, likewise, represented the pinnacle of manuscript illumination in the early fifteenth century, working with Berry until their untimely deaths. The third figure in the Judges panel thus becomes a pivot point between two artistic lineages: the Eycks and the Limbourgs, both trios of brothers who redefined the visual culture of the Burgundian court.

Figure 6: Right: *Paul Limbourg - Self Portrait - Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry Janvier (1416)

Figure 6: Right: *Paul Limbourg - Self Portrait - Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry Janvier (1416)

The presence of a third artist frames the Ghent Altarpiece as part of a broader genealogy of Northern art, where kinship and collaboration fed into a lineage that outlasted any single hand. The comparison between the Limbourgs' unfinished Très Riches Heures and the Eycks' completed altarpiece would not have been lost on contemporary viewers. Barthélemy's or Paul's presence in the procession implies continuity: just as one generation of brothers left their masterpiece unfinished, another stepped in to bring monumental projects to completion. The Just Judges thus becomes a meditation on artistic succession and mortality. It asserts that the work of sacred art is never truly the product of a single hand but of a lineage, where brothers, collaborators, and heirs collectively advance the craft. In positioning themselves within this chain, the van Eycks subtly elevate the role of the artist to one of divine witness, judges not of men but of images, responsible for preserving memory across time.

Figure 7: Right: *Paul Limbourg - John, Duke of Berry - Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry Janvier (1416)

Figure 7: Right: *Paul Limbourg - John, Duke of Berry - Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry Janvier (1416)

The Mad King

Figure 8: Right: Pierre Salmon - Charles VI (1415)

Figure 8: Right: Pierre Salmon - Charles VI (1415)

Charles VI of France, crowned in 1380 at the age of eleven, embodied the instability of a monarchy undone from within. His reign began under the promise of unity but quickly descended into fragmentation as recurring bouts of mental illness left him unable to govern. By 1392, his breakdowns were frequent and violent enough to earn him the epithet "Charles the Mad." The French crown, already strained by the aftershocks of the Hundred Years' War and economic unrest, now suffered the indignity of being effectively leaderless. In the vacuum that followed, Charles's uncles stepped in to exercise authority: Louis of Anjou, John of Berry, Philip the Bold of Burgundy, and Louis II of Bourbon. Each acted not as a guardian of the realm but as a rival prince, carving out spheres of influence while cloaking their ambition in the rhetoric of regency. Van Eyck's inclusion of these figures in the Just Judges panel situates the king as the unstable pivot around which competing dynastic forces orbited.

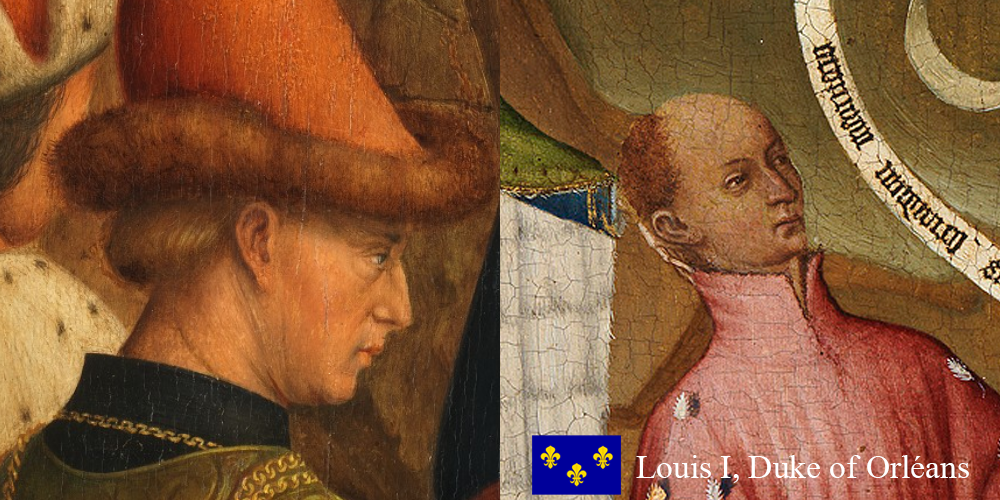

Figure 9: Right: Colart de Laon - Louis I of Orléans (1408)

Figure 9: Right: Colart de Laon - Louis I of Orléans (1408)

The king's younger brother, Louis I, Duke of Orléans, looms in van Eyck's composition above and behind Charles, signaling his opportunism and ambition. Closely allied with Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, Louis of Orléans was widely rumored to have been her lover, a scandal that only sharpened his hunger for influence at court. His presence intruding into Charles's visual space in the panel suggests the violation of both familial and royal order. The red hat that Charles wears, his "nest", is symbolically compromised by his brother's encroachment, an allegory of how Louis and Isabeau's partnership hollowed out the authority of the crown. In this reading, the king becomes not the arbiter of justice but its victim, his sanctity as monarch invaded by fraternal rivalry. Van Eyck's allegory echoes the reality of the period: France was less governed than contested, its royal household consumed by whispers of adultery, betrayal, and treachery.

Figure 10: Right, Clockwise: Rogier van der Weyden - Philip the Good (1445), Anonymous - John the Fearless (~1405), Jean Malouel(?) - Philip the Bold (~1400)

Figure 10: Right, Clockwise: Rogier van der Weyden - Philip the Good (1445), Anonymous - John the Fearless (~1405), Jean Malouel(?) - Philip the Bold (~1400)

By condensing the three Burgundian dukes into one figure, van Eyck dramatizes the dynastic succession that unfolded over Charles's reign. Philip the Bold's death in 1404 shifted the balance of power, elevating his son John the Fearless. Yet John's reduced influence at court allowed Louis of Orléans to dominate the regency with Queen Isabeau. John of Berry, the elder statesman, tried to mediate between these factions, but his efforts could not contain the animosity. The rivalry hardened into open conflict between the Armagnacs, aligned with Orléans, and the Burgundians under John the Fearless. By depicting these dukes clustered around Charles VI, van Eyck stages the very moment when royal authority disintegrated into factional violence. The Mad King, seated in fragile dignity, becomes less a sovereign than the canvas upon which rivalries were inscribed. His weakness precipitated the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War, and in the Just Judges, this political catastrophe is encoded in allegorical form, showing how earthly rulers, for all their crowns and brooches, ultimately failed the divine justice they claimed to uphold.

The Assassinations

Figure 11: Murder of the Duke of Orléans, illumination on parchment by the Master of the Vienna Chroniques d'Angleterre (~1470)

Figure 11: Murder of the Duke of Orléans, illumination on parchment by the Master of the Vienna Chroniques d'Angleterre (~1470)

The assassination of Louis I, Duke of Orléans, stands as one of the most shocking acts of political violence in late medieval France, and its aftermath permanently split the kingdom. John of Burgundy, later called "the Fearless," orchestrated not only the killing but also the narrative that followed. His propaganda machine worked relentlessly to portray Louis as corrupt, extravagant, and morally bankrupt. Louis was accused of overtaxing the people to fund his excesses, of seducing countless women, including John's wife Margaret of Bavaria, and even of fathering Charles VII with Queen Isabeau. These accusations, whether wholly fabricated or exaggerated, cast Louis as the embodiment of aristocratic vice. John, in contrast, positioned himself as a reformer, a champion of the Estates General, and a man of the people. The irony was brutal: John himself was every bit as greedy and ambitious as his cousin, but he understood that controlling the story of power was as important as controlling power itself.

The murder itself was theatrical in its cruelty. On the evening of 23 November 1407, Louis had paid a courtesy visit to Queen Isabeau, who had recently given birth. As he left the Hôtel Barbette, he was lured toward the Hôtel Saint-Paul under the false pretense that the king urgently awaited him. There, in the dark streets of Paris, his party was ambushed by 15 to 20 masked men. The attack was swift and grotesque: Louis's arms were hacked off to prevent resistance, his skull crushed so violently that, as chroniclers recorded, his brains spilled onto the cobblestones. The brutality was not incidental, it was meant as a message. This was not the quiet removal of a rival but a public spectacle of annihilation, calculated to terrorize supporters and cement John's reputation as a man who would do whatever was necessary to assert dominance.

By eliminating his rival so savagely, John set into motion the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War, which would convulse France for decades. The assassination revealed more than personal enmity: it showed how fragile the French monarchy had become under Charles VI's madness. Without a stable king, the kingdom fell hostage to the ambitions of princes who treated political authority as spoils to be fought over with axe and dagger. Van Eyck's Just Judges panel, in its veiled allegories, encodes precisely this dynamic: rulers arrayed in their finery, yet beneath the surface, driven by envy, propaganda, and violence. The murder of Louis ended one life and began a fratricidal struggle in which the ideals of justice collapsed into blood on the Parisian stones.

The Rebuttal

The aftermath of Louis of Orléans' murder revealed John the Fearless's genius not only for violence but for narrative control. France reeled at the brutality of the crime, taxes might have made Louis unpopular, but his sudden butchery on the streets of Paris was unthinkable. To most, the deed crossed the boundaries of kinship, law, and sanctity: the killing of a prince of the blood by another prince was nearly regicidal in its implications. Yet John did not retreat into silence. Within days, he launched a public defense, framing himself not as a murderer but as an agent of divine justice. This was propaganda of the highest order: swift, systematic, and intellectualized. It transformed a scandal into a moral argument.

The Justification du duc de Bourgogne, delivered in Paris and circulated across the kingdom, recast the assassination as tyrannicide. Louis was painted as a tyrant who had corrupted the queen, bled the treasury, practiced sorcery, and plotted to usurp the throne. By striking him down, John claimed, he preserved the monarchy from collapse. John Petit's celebrated oration before the court in March 1408 carried this rhetoric to its climax, declaring that the act was lawful, godly, and even meritorious. Biblical precedents, classical philosophy, and scholastic logic were marshalled to baptize the killing as righteous. It was sophistry, but it worked: rather than being condemned, John became a figure of fear and awe, earning the epithet "the Fearless" not from battlefield heroism but from his brazen justification of political murder. Had Charles VI been capable of judgment, John would have been executed. In the void left by the king's madness, however, the assassin stepped forward as the kingdom's de facto arbiter of justice.

Figure 12: Right: Pisanello - Portrait of Sigismund of Luxemburg (1433)

Figure 12: Right: Pisanello - Portrait of Sigismund of Luxemburg (1433)

Beyond France's borders, others attempted to moderate the escalating feud. Sigismund of Luxembourg, then King of Hungary and later King of the Romans, cast himself as a mediator between the Burgundians and the Armagnacs. His authority mattered because Burgundy remained formally within the Holy Roman Empire's orbit, and imperial arbitration carried symbolic weight even when it lacked practical enforcement. Sigismund's interventions echoed those of John, Duke of Berry inside France: both tried to hold the kingdom's fracturing nobility together, both ultimately failed. Yet his presence in the Just Judges procession acknowledges that this was not merely a French crisis but a European one, in which emperors as well as kings were imagined as judges riding toward the Lamb.

Figure 13: Top Right: Illuminated miniature, Henry IV (1402). Bottom Right: Thomas Hoccleve - Illuminated miniature, Henry V (~1412)

Figure 13: Top Right: Illuminated miniature, Henry IV (1402). Bottom Right: Thomas Hoccleve - Illuminated miniature, Henry V (~1412)

Van Eyck's inclusion of England in this allegorical procession deepens the scene's irony. At the top left of the panel, a shadowed figure represents both Henry IV and his son Henry V, each marked by physical disfigurement, psoriasis for the father, a battlefield arrow scar for the son. Their veiled faces are reminders of how kingship itself was often scarred, vulnerable, and precarious. For John the Fearless, these monarchs were not enemies to be resisted at all costs but variables to be managed. He courted English neutrality by manipulating the vital wool trade of Flanders, always ensuring that his grip on power in Paris mattered more than resistance to foreign invasion. His stance was one of calculated ambiguity: never openly betraying France to England, but never truly committing to defend it either. In this sense, van Eyck's panel mirrors the reality of French politics in the early fifteenth century, where justice was less about divine order and more about survival, propaganda, and the willingness to turn murder into doctrine.

Revenge

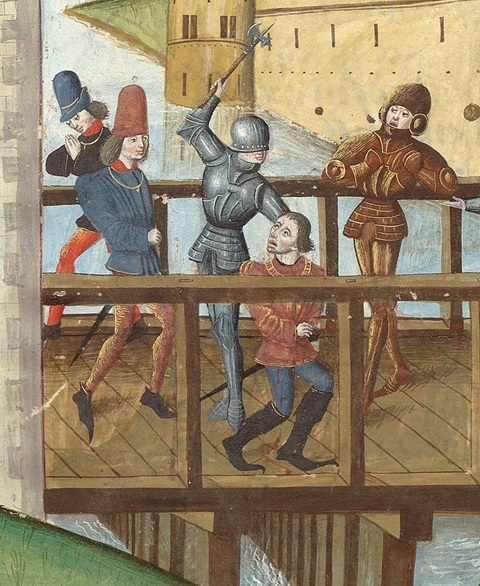

Figure 14: The Chronicle of Enguerrand de Monstrelet - Assassination of Duke John the Fearless on the bridge of Montereau (~1440s–1470s)

Figure 14: The Chronicle of Enguerrand de Monstrelet - Assassination of Duke John the Fearless on the bridge of Montereau (~1440s–1470s)

The bridge at Montereau in September 1419 brought the long feud between Orléans and Burgundy to its violent climax. Ostensibly, John the Fearless came to reconcile with the Dauphin Charles, but neither party approached the meeting in good faith. John's finances were strained and he sought breathing room, while Charles's men viewed the Burgundians as duplicitous collaborators with England. The encounter was less a negotiation than a staged confrontation, brimming with suspicion. When John raised his sword in a gesture interpreted as hostile, the Armagnac knight Tanneguy du Chastel struck him down with a single axe blow to the head. The man who had once justified political murder now became its victim, bleeding out on the planks of the bridge he had entered as mediator.

The assassination shocked contemporaries not only for its brutality but for its futility. The Armagnacs claimed self-defense, but no one truly believed them. John's death stained the reputation of the Dauphin's faction, undermining their claim to embody lawful resistance. Rather than restoring stability, the murder deepened the chaos. His son Philip the Good, inflamed by vengeance, sealed a formal alliance with the English. The consequences were devastating: the Burgundians, who had once posed as France's internal reformers, now became accomplices to foreign occupation. The civil war that began with John's orchestrated killing of Louis of Orléans ended with his own murder, but it did not resolve the divisions of the realm. Instead, it dragged France deeper into the Hundred Years' War at the very moment the kingdom was most fractured.

Only the Congress of Arras in 1435 began to heal the wound. By then, Charles VII had secured his coronation at Reims and regained momentum against the English. Philip the Good formally recognized him as king while extracting extraordinary concessions: exemption from homage and a promise, never fulfilled, that the Dauphin would punish John's killers. The irony was complete. Two generations of murder had not advanced justice but had left France weakened, its soil bloodied by both civil war and foreign invasion. In van Eyck's Just Judges, the figures of John the Fearless and Philip the Good ride solemnly toward the Lamb, their historical reality undercutting their allegorical role. Painted as righteous rulers, they were in fact heirs to a legacy of treachery and revenge that delayed France's deliverance for nearly two decades.

Joan

Figure 15: Right: Joan of Arc (late 19th-century art forgery)

Figure 15: Right: Joan of Arc (late 19th-century art forgery)

Joan of Arc's fate cannot be disentangled from the civil war that tore France apart in her own lifetime. When she rose to prominence in 1429, she was stepping into a battlefield shaped as much by Burgundian treachery as by English aggression. Her victories at Orléans and the coronation of Charles VII at Reims directly repudiated the Treaty of Troyes, which had disinherited the Dauphin and handed succession to the English crown. To the Anglo-Burgundian alliance, Joan was not merely a military threat but a theological one. Her presence suggested that God Himself had chosen sides, sanctifying Charles's kingship. That is why her capture in 1430 by Burgundian troops was so consequential: she was not taken by the English, but sold to them by their French allies, her body and soul transformed into a political transaction.

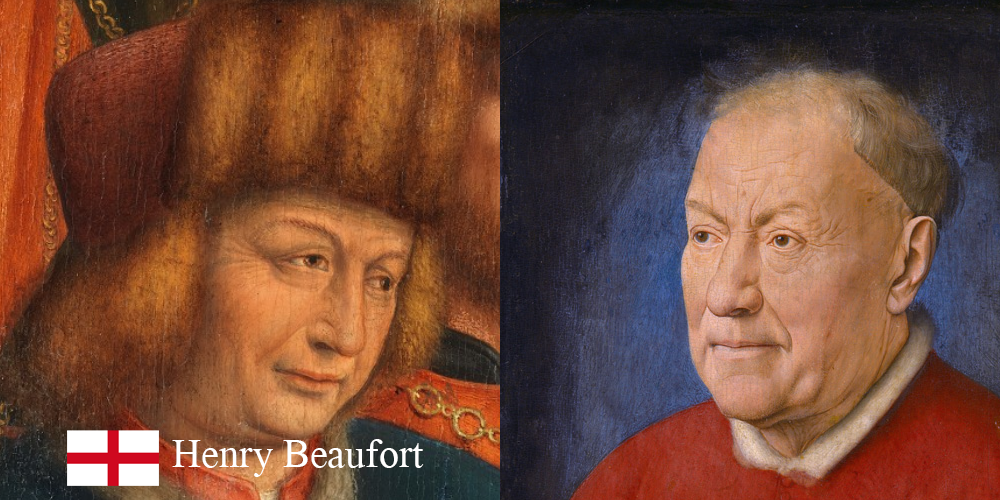

Figure 16: Right: Jan van Eyck - Portrait of Henry Beaufort (1431)

Figure 16: Right: Jan van Eyck - Portrait of Henry Beaufort (1431)

The machinery of her trial reveals just how closely the Burgundians wove law, religion, and propaganda into their campaign against the Armagnacs. Pierre Cauchon, the Burgundian bishop of Beauvais, claimed jurisdiction solely because Joan had been captured within his diocese, a legal maneuver that ensured she would be tried in Anglo-Burgundian custody rather than in any neutral or Armagnac-leaning venue. His hearings were never about Joan's conscience but about Charles VII's legitimacy. If she could be branded a heretic, then the Reims coronation she had enabled could be portrayed as tainted. Henry Beaufort, Cardinal of Winchester and uncle to the young Henry VI, guaranteed that the English crown had both the authority and resources to see the case through. His visible presence at her condemnation and execution sealed the trial as a spectacle of statecraft: a Frenchwoman burned in Rouen to declare that France belonged to England and Burgundy.

Against this backdrop, the completion of the Ghent Altarpiece acquires added resonance. Hubert van Eyck's death in 1426 left Jan with the task of finishing the polyptych, and the Just Judges panel, almost certainly the last to be painted before the 1432 unveiling, bears the full stamp of Jan's authorship. Its theme, earthly rulers riding in judgment toward the Lamb, was painted at precisely the moment Joan's trial was turning the question of legitimate kingship into a cosmic battleground. Cauchon and Beaufort staged Joan's death as a divine judgment against rebellion; Jan staged his panel as a meditation on how rulers, for all their pomp and finery, must ultimately answer to a higher tribunal. In both cases, judgment was the contested ground, whether through fire in Rouen or paint in Ghent. This convergence of politics, theology, and art makes clear that the Just Judges reflects not an abstract allegory but the very world Jan van Eyck inhabited.

Mystery

Arsène Goedertier

Figure 17: Arsene Goedertier (20th century photograph)

Figure 17: Arsene Goedertier (20th century photograph)

On the morning of April 11, 1934, Saint Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent awoke to scandal. The sexton, arriving to begin his daily duties, noticed that the door stood ajar and, inside, something was clearly amiss. As he pulled aside the curtain shielding the Ghent Altarpiece, the city's most prized artistic treasure, he froze. Two panels, The Just Judges and Saint John the Baptist, had been removed from the polyptych's lower tier. Their absence was glaring, leaving empty frames where centuries of devotion and pride had once resided. The news of theft spread like wildfire through Ghent, shocking not only parishioners but all of Belgium. Police were called, but the scene had already been compromised by the curious public streaming through the cathedral. No usable evidence was found, save for a small note pinned to the frame that read, in French: "Taken from Germany by the Treaty of Versailles." It was a statement as cryptic as it was provocative, suggesting the crime was not merely theft for profit, but an act staged in the shadow of Europe's bitter postwar settlements.

The investigation seemed to stall until, three weeks later, a letter arrived on the bishop of Ghent's desk. The envelope was a peculiar pastel green, and the letter within was signed "D.U.A.", a pseudonym whose meaning has never been satisfactorily explained. Written in formal, almost courteous language, the author declared that he possessed the two stolen panels and would return them only in exchange for a ransom of one million Belgian francs. The demand was accompanied by threats: failure to comply would lead to the destruction of the missing works. The Belgian government hesitated, wary of setting a precedent, but the bishop continued cautious correspondence. In an act meant to prove both control and goodwill, the thief soon returned one panel, Saint John the Baptist, unharmed. A coded message led police to a baggage locker at Brussels North station, where the panel was found carefully wrapped. This confirmed that the thief was both serious and sophisticated, capable of leveraging the paintings like hostages in a long negotiation.

Encouraged but wary, investigators pressed on. D.U.A. now made a bizarre request: the ransom was to be funneled through an unsuspecting intermediary, Father Henri Meulepas of Antwerp's St. Lawrence Church. Meulepas, confused and embarrassed, protested ignorance of any connection to the affair, but agreed to cooperate with authorities. A package containing 25,000 francs, barely a fraction of the sum demanded, was prepared as a test. A taxi driver later arrived at the priest's doorstep to collect the parcel, his instructions written in another note from D.U.A. The driver departed quietly, and the trail went cold. Witness testimony from station clerks and Meulepas's maid provided a vague description of a middle-aged man with a pointed beard, but no arrests were made. A series of further letters followed, suggesting the thief might accept a lower ransom, yet correspondence abruptly ceased on October 1, 1934. The negotiation collapsed, leaving only the returned Baptist panel as proof of progress.

The mystery deepened eight months later with the sudden death of Arsène Goedertier, a 57-year-old stockbroker, former sexton, and respected Catholic politician from Wetteren. During a political rally he suffered a fatal heart attack, and on his deathbed he summoned his lawyer. With his final breaths, Goedertier confessed that he alone knew the location of The Just Judges. "In my desk... key... cupboard... folder Mutualité," he muttered, before expiring. When the lawyer followed these instructions, he discovered a folder containing drafts of thirteen ransom letters, along with meticulous clippings of every newspaper article on the case. No panel was found, nor any map or explicit confession. Goedertier's involvement was undeniable, yet the ultimate fate of the panel remained hidden. Whether he had stashed it in the cathedral itself, entrusted it to confederates, or hidden it somewhere in the city, Goedertier took the secret with him. His half-confession turned a baffling theft into a national obsession.

In the decades since, theories have proliferated. Some suggested Goedertier had intended to return the panel but was overtaken by illness. Others implicated Jef Van der Veken, the skilled restorer who produced the official copy still on display today. Because Van der Veken's replica was so masterful, rumors circulated that he had somehow gained access to the original, even painting over it and passing it off as a reproduction. Nothing was ever proven. Investigations have continued into the present: pavements have been drilled, cellars searched, and even walls of Saint Bavo's Cathedral probed for hidden chambers. Yet every effort has ended in disappointment. What remains is an unresolved riddle at the intersection of art, crime, and national pride. Nearly a century later, The Just Judges is still missing, its absence as conspicuous as the empty space it left behind in Jan van Eyck's masterpiece. Until another confession emerges or the panel is stumbled upon by chance, the mystery endures as one of Europe's most haunting cultural cold cases.

Jef Van der Veken

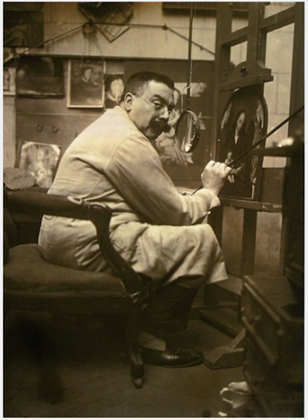

Figure 18: Jef Van der Veken restoring a Metsys (1929)

Figure 18: Jef Van der Veken restoring a Metsys (1929)

Jef Van der Veken's replica of The Just Judges, completed in 1945, has long stood in place of Jan van Eyck's missing masterpiece. A highly skilled restorer and forger of early Netherlandish painting, Van der Veken was known for his uncanny ability to reproduce fifteenth-century techniques, down to pigments, glazes, and even the craquelure of aged varnish. His copy of The Just Judges is so persuasive that, for most visitors to Saint Bavo's Cathedral, it functions seamlessly within the Ghent Altarpiece. Yet precisely because of his reputation and the near-perfect fidelity of the work, suspicion has lingered that Van der Veken was not merely copying, but concealing.

The core theory is that Van der Veken painted his "replica" directly on top of the original panel. Proponents point to several circumstantial factors. Van der Veken's studio access and restoration authority would have given him a legitimate pretext to handle and transport the painting, had it resurfaced discreetly. His known penchant for retouching originals until they were virtually unrecognizable, so-called "hyper-restorations", further fuels the idea that he might have disguised the authentic Judges beneath his brushwork. Moreover, critics note that the Belgian state and the Church had every incentive to accept his reproduction as genuine substitution, while quietly ignoring the uncomfortable possibility that the original still existed. In this light, Van der Veken's replica becomes not just a replacement, but a potential tomb for the vanished panel.

Perhaps the most tantalizing piece of evidence is the cryptic poem Van der Veken inscribed on the back of his copy:

"I did it for love

And for duty

And to avenge myself

I borrowed

From the dark side"

Interpreting these lines has become its own sub-discipline of speculation. "Love" and "duty" may refer to his devotion to Flemish art and his role in restoring a national treasure in the wake of war. "To avenge myself" could echo his frustrations with critics who dismissed his artistry as derivative, or with institutions that denied him full recognition. The most enigmatic phrase, "I borrowed from the dark side," invites sinister readings: did he mean he borrowed literally from the "dark side" of the canvas, the hidden original beneath his copy? Or was it a metaphor for his forger's craft, the skill of deception he honed in the shadows? The poem offers no definitive key, but its ambiguity seems almost designed to perpetuate the legend.

Ultimately, the fascination with Van der Veken's replica reflects the discomfort of a cultural wound that has never healed. If he truly overpainted the lost Just Judges, then the panel has been hiding in plain sight for decades, visible yet invisible, a paradox as vexing as Goedertier's dying words. Even if the inscription is nothing more than a self-mythologizing flourish, it perfectly captures the air of secrecy and mischief that continues to shroud the mystery. Van der Veken, whether restorer, forger, or secret custodian, ensured that the absence of the Judges would never feel fully empty.

Succession

The story of The Just Judges is, at its heart, about succession, both dynastic and artistic. Within the Ghent Altarpiece, the panel embodies the earthly procession of rulers, magistrates, and princes who carry forward the burdens of power, echoing the divine and cosmic order depicted elsewhere in the polyptych. Painted by Jan van Eyck after Hubert's death, it represents not only the succession of earthly rulers, but the succession of artistic genius itself, as the younger brother completed and perfected the work that Hubert began. To lose this panel, therefore, was to lose the fragment of the altarpiece that most explicitly spoke to the passage of authority, the inheritance of legitimacy, and the fragile continuity of human institutions.

The theft of 1934 layered another kind of succession onto the painting's fate: a mystery within a mystery. The act itself was precise and theatrical, cloaked in the rhetoric of Versailles and international grievance. The ransom letters signed "D.U.A.", the partial restitution of Saint John the Baptist, and the deathbed murmurings of Arsène Goedertier transformed the theft into something more than an unsolved crime. It became a narrative passed down like an heirloom, with each new investigator, theorist, or amateur sleuth inheriting the riddle and adding their own chapter. In this way, the theft mirrors the panel's theme of succession, for the mystery itself has been "bequeathed" across generations, each grappling with the absence and the unanswered question: where are the Judges?

That absence, material, historical, and symbolic, has made The Just Judges into one of the most haunting cultural enigmas of Europe. Theories abound, from Van der Veken's replica concealing the original, to Goedertier's hidden cache still waiting to be uncovered. Yet the very irresolution of the case ensures its power. The panel about succession has itself become subject to the succession of mysteries, a loss that refuses to close. In this way, the story of The Just Judges is a testament to how art, politics, and myth pass from one era to the next, unfinished, carrying forward the same anxieties about legitimacy, justice, and inheritance that Van Eyck painted nearly six centuries ago.